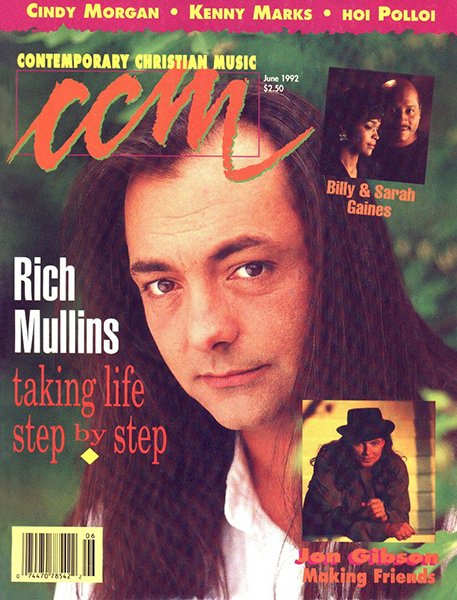

Step By Step: A Conversation with Rich Mullins

by Brian Quincy Newcomb

CCM Magazine June 1992

Rich Mullins took the stage for his GMA showcase with his hands stuffed in his jeans, while Billy Crockett and his band of studio players worked through the acoustic-driven "Boy Like Me / Man Like You," one of the opening songs from his two-album piece The World as Best as I Can Remember It. Before the brief concert was over, Mullins was playing a hammer dulcimer as he sang, the band was playing a pop arrangement that moved toward dramatic drumming from the Paul Simon school, and an African-American church choir was augmenting Mullins' vocals with gospel heart and soul. In this simple, bold, artful way, Rich Mullins unleashed a quiet, thoughtful revolution.

A couple days later, Mullins and I had occasion to enjoy a country breakfast at Nashville's landmark Loveless Cafe. We talked about growing up male, growing up in the church, and not really wanting to grow up at all. We drank lots of coffee and spoke of the world as best as we could remember it.

We talked about a life of serving God's church and its mission in the world, we talked about working in the world of contemporary Christian music, about making art that speaks honestly about humanity and tells the truth of God's dramatic love, and we tried not to bore my wife.

We also managed to talk about Mullins' latest album, Volume Two of The World as Best..., and about writing music that "accidentally" gets on Christian radio, about trying to make sense of your birth family, and making sense of God's church, the adopted family of faith. We tried to tell the truth - Rich was Earnest, I tried to be Frank - we talked about the importance of being Frank and Earnest. Recounted here are the highlights, as best as my tape recorder remembers it.

BQN: It seems that trying to encapsulate all you know about life into two albums is a pretty lofty goal. Did you get it all down in the two albums, or should we look for Volume Three?

RM: I think sometimes I have a tendency to be a little overly idealistic and I want to see the world the way that I think it ought to be. I guess a lot of what the albums are about is saying "instead of starting out with a dismal view of the world, or a happy view of the world, what is there?" And let me see what is really there and maybe it'll have some effect on the way I view the rest of my life.

I didn't sit down and write 20 songs about the way the world really is, but it's kind of been the thing that I've been working on personally, which finds itself working out in your songs. It accidentally has an autobiographical feel. I think a lot of the songs on Volume Two are a little more adult-ish.

With "Step by Step," if I had to make an overall statement, it's that faith is walking with God. The biggest problem with life is that it's just daily. You can never get so healthy that you don't have to continue to eat right. Because every day I have to make the right choices about what I eat and how much exercise I need.

Spiritually we're in much the same place. I go on these binges where it's like "I'm going to memorize the five books of Moses." I expect to be able to live off the momentum. The only thing that praying today is good for is today. So, with "Step by Step" and "Sometimes by Step," it's not what you did, and not what you say you're going to do, it's what you do today.

BQN: You've managed to get a lot of airplay, and by many standards you've become very successful at what you do. Still, there's this feeling that you're not all that comfortable with that reading of the way things are.

RM: I'm afraid that in the Christian church in America there's this understanding that life has meaning basically with the success that God gives us in life. Looking at the scheme of God's history with people, success and failure are pretty meaningless. Meaning in life is somehow beyond the way that we measure success, and that's kind of a relief for me, to know that the weight of the world is not on my shoulders. For me there needs to be a return to the doing of things for the sake of doing them, and not for the sake of being great at it. G. K. Chesterton said, "Anything worth doing, is worth doing badly." It took me a long time to get that, I thought he was just being smart. But, I realized that what he was saying was "So what; you're not going to get a job as a caterer - learn how to cook."

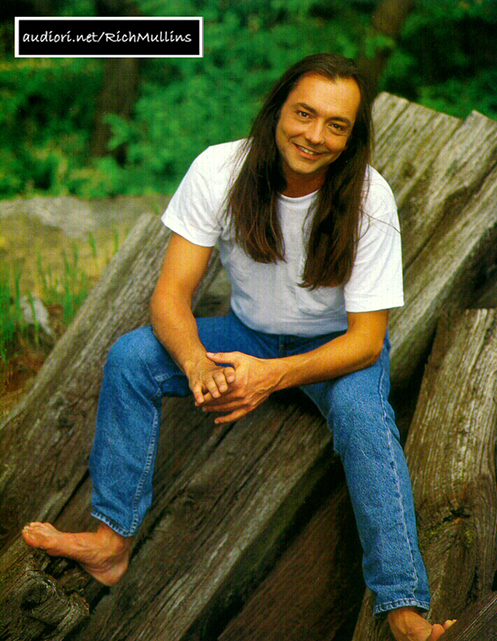

(Photo by Mark Tucker.)

BQN: Something I often hear when people mention your name is that you're celibate, like you're the Apostle Paul or Morrissey or something. I always figure that must be some kind of an excuse for not being able to get a date to the Dove Awards (laughter).

RM: My take on this is, for those people who are too weak to handle celibacy, God gives a spouse. People who are too weak to handle a spouse, God gives celibacy. So, I'm pretty comfortable, and I wouldn't mind being married. Especially from 10 to 2. I'm happy..., but I also believe that if you're not happy where you are you're not going to be happy anywhere. If I have a problem, I'd like to be able to be aware of it before I get married, because I'd hate to enter into it with the illusion that if I get married I'll never be lonely again. Or the illusion that someone will always love me. I know a lot of very lonely married people.

BQN: On your tour with Sparks you opened your show with an a cappella take on Handel's "Hallelujah Chorus," arranged like The Roches. You've consistently used dulcimer and bag pipes and other instrumentation unusual to the pop song format. How interested are you in ethno-musicology, and why do you think that this thing works so well with Christian music audiences?

RM: I really don't know. Lucille Ball once said that she got the roles she got because she would do anything; that other comedians wouldn't make the faces that she would make, and I kind of think that's the case with me. A lot of people have too much sense to do the kind of thing I'm doing. I'll tell you where my original musical interests came. Growing up, I had piano lessons since I was real little. I had a very good music teacher, Mary Kellner, who not only introduced me to some of the great composers, but she was able to capture my imagination and make me excited about what I was supposed to be learning.

Now my dad was an Appalachian, which is a very polite way to say that he was a hillbilly, and in junior high I was always embarrassed about my dad. He never dressed right, he never had a suit that fit him, and always had dirt or grease under his fingernails.

In my junior year of high school we went to a funeral in Kentucky where my dad had grown up. It was one of those times - people say to me "Did you ever have a born again experience?" and I always say "frequently." My dad, who wasn't a sentimental, gushy kind of guy, pulled off the road. We walked around for a bit, and my dad said, "This is all changed. Somewhere out here there was a swimming hole and a vine we used to swing out over the water on." And I suddenly realized that my dad had been a kid once. At the time the most convicting verse in the Bible was "Honor your father and mother." And I realize now that [that verse] means that if you cannot honor your father and mother then you can't honor anybody. Until you come to terms with your heritage you'll never be at peace with yourself. That was a real breakthrough moment for me.

So, what I needed to do was come to understand the Appalachian life, so that I could know more about my father, who had been a stranger to me all my life. When I went to college I was able to start collecting Appalachian music. After I got over that fear of spending 45 minutes listening to an album that wasn't pop or rock, I realized that there was a lot of terrific music in the world.

BQN: Single-handedly you've brought the hammer dulcimer to the attention of a generation of Christian music fans who might not know of it's beauty.

RM: For me, one of my greatest accomplishments that I'm most proud of is "My One Thing," which was written and performed on a hammer dulcimer, and went to Number One on pop Christian charts. How many hammer dulcimer songs are there - and this goes to Number One. That's weird.

BQN: Early on you began writing with people like Amy Grant. I remember being pretty impressed by "Love of Another Kind." Did you originally want to be a writer who had hit songs?

RM: When I came here, I was working with Randy Cox [now with Sparrow Publishing] and I touted myself as an artist. And I was very pretentious. Randy would beat me over the head and tell me I needed to write commercially: "If you're going to do art go to New York or somewhere else, but this is Nashville."

I finally decided that instead of taking commercial writing as something cheap, I began to ask, "Can I say something in an easily accessible way, and still say something significant?" I don't want to sell out, to be a commercial writer. I want to be better than a commercial writer, I want to be better than an artist. I want to do both things. I want to say something significant. I still want to say what I believe and what I feel honestly, but I want people to be able to relate to it. That's kind-of an impossible goal.

BQN: You've had some wonderfully honest songs. What's one of your favorites?

RM: My favorite song that I've ever written is "Elijah." It was like another breakthrough. I wrote it around the time when John Lennon was shot. He was a big hero of mine, and my great-grandma died about the same time. I began thinking about the influence both of those people had on my life, and they were dead. These two people would never know the impact they had on me; John Lennon I'm sure wouldn't care to know, but my great-grandma, I never got to tell her. But then I realized I don't have to tell her. She didn't do what she did to have some kind of an impact on me, she did what she did because that's who she was.

And I'm going to be dead someday too. That's the first song where I forced myself to dig under a lot of the cliches of the Christian faith. I wrote a song that said, "You know, someday I'm going to die, and I wanna die good." Prior to that I would have tended to write, "Someday I'm going to die and I will be resurrected," which I also believe.

BQN: I've heard some funny stories about your shows. Like once in Chicago, you walked out barefooted before the lights dropped and just sat down at the piano and started to play before anybody realized you were on the stage and not just some roadie.

RM: I find it embarrassing to be introduced. When I was in fourth grade, I got asked to play the communion meditation at church. I practiced and my piano teacher worked with me, which was cool because she was Quaker, and they don't even have communion. Anyway, I went back Tuesday to my lesson after I had played Sunday, and my teacher said, "How did you do?" and I told her, "Everybody said they loved it, everyone said I did great." And she said, "Well, then you failed." I was crushed, but she put her hand on my shoulder and said, "Richard, when you play in church, you are to direct people's attention to God, not to your playing."

Ever since then there's something about "And now, Ladies and Gentlemen, Rich Mullins," and I keep thinking that Mary Kellner's going to come up and say, "Now Richard, when you play in church..." I'm enough of an egomaniac that I want people to go away and go, "Wow, he's great." But I may not be great enough to accomplish that... I know I can be humble! (great laughter)

BQN: You make lots of literary references. How influenced is your writing by the things you read?

RM: Well, what I write certainly isn't as good as what I read. The thing I find attractive in people I like to read is that they're just brave enough to say what they really think. I think we all get hung up in saying something that is unique, but we may miss saying something clearly, or accurately. It's like C. S. Lewis said, "The idea is not how unique your idea is, or how unique your expression is, the idea is to take what is common and to freeze it in a moment." And that's kind of what I relate to in the writing of other people.

My goal - the thing that I respond to in writing and the thing that I would like to accomplish - would be to say things exactly as they are; to give the most accurate description possible. So many people are distressed by [the song] "Jacob and Two Women," and I respond, "then the Bible must be very distressing to you."

I think that we live in a real information and answer oriented world, and the thing that I'm discovering from reading the Bible is that it's not always what they taught us in Sunday School. For instance, I was taught that Esther was a queen, but reading the account myself I've learned that Esther was the head harem girl. Our attempt is to make Esther into a nice woman, but that's not accurate.

Not a concert has gone by when somebody hasn't come up after "Jacob and Two Women" and said, "Man, I don't get that song." And I don't get it either, except that a man married two women and had his hands full. And I do think it's very lovely that the only child of his 12 sons that Jacob named was Benjamin. Rachel died giving birth to Benjamin, only her second child. So here she is dying after giving birth, and she names him Ben-o-me, which means son of my sorrows. But Jacob says, "I won't call him that, but I will call him Benjamin, which means son of my strength." As if to say to Rachel, "Your beauty is my strength. You are not just a beautiful woman, you are my strength."

BQN: I keep hearing that you've given 10 years to your music and ministry, and that this is your last tour before you go off to serve God in mission work....

RM: Well, I do intend to go back to school and finish my degree, it's either now or never. As I get closer to 40, I realize that there are a lot of other things I still want to be able to do in my life. I want to finish college and be able to teach music therapy to native American kids on reservations. That's such a high risk situation.

I love making records, it's a lot of fun. It's a little embarrassing but sometimes I think - and here's the worst ego statement of the day - "who'll do this if I don't?" It seems there are people who like what I do. And, I like being liked. I've had plenty, and if I were not able to do this anymore I would be happy. But I don't want to lock myself into or out of anything. I'm kind of aware that we're all capable of a lot more than we think.

It's a matter of priorities: [Frederick] Buechner says, "Your calling is the place where your deepest joy and the world's greatest needs cross." For me, the greatest joy that I have is knowing that I do have a Father who loves me, and that he doesn't love me in a passive way. That he loves me so much that he sent Christ to take away the guilt of my sin and that it is a real thing, that it really did happen.

If I will experience joy in this life it will be when I let other people know that there is a God who loves them, and he has taken away the sin that separates them. There is no greater joy than just that proclamation.